Biography tells us that Hill aspired to hoodlumhood from the age of 12. His problem was that he wasn't 100% Italian — his father was Irish, his mother Sicilian — but that didn't stop him from giving it the good ol' college try. The Luchese crime family ruled Hill's neighborhood and Hill became involved in gambling and the drug trade. One of the organized crime figures involved was Henry Hill, who was the subject of the movie, 'Goodfellas.' The Chicago Black Sox Scandal Top Tenz. Was an important member of the ‘Lucchese crime family,' which executed organized crime throughout New York City from 1955 to 1980. Towards the end of his life, Henry pursued various non-criminal endeavours, such as writing books, painting, selling paintings on eBay, cooking, managing a restaurant, counselling, appearing in TV. Henry Hill (born June 11, 1943 - June 12, 2012) was a former American mobster, Lucchese crime family associate, and FBI informant whose life was immortalized in the book Wiseguy, written by crime reporter Nicholas Pileggi, and the 1990 Martin Scorsese film GoodFellas, in which Hill was played by actor Ray Liotta. 1 Ancestry 2 Early life 3 Early criminal career 4 Fallout between Hill, Vario. Martin Scorsese's Oscar-winning 1990 crime drama Goodfellas, inspired by the true story of Irish-Italian mobster-turned-state's witness Henry Hill, is widely considered one of the best.

United States v. James Burke, Louis Lopez and Henry Hill, United States of America v. Raul Charbonier and Luis Charbonier, 495 F.2d 1226 (5th Cir. 1974)

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

495F.2d1226

UNITED STATES of America, Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

James BURKE, Louis Lopez and Henry Hill, Defendants-Appellants.

UNITED STATES of America, Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

Raul CHARBONIER and Luis Charbonier, Defendants-Appellants.

Henry Hill Casino Mob Documentary

Nos. 72-3742, 73-1045.

United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit.

June 12, 1974, Rehearings Denied Aug. 9, 1974.

Barry A. Cohen, Paul Antinori, Tampa, Fla., for James Burke et al.

Raymond E. LaPorte, Tampa, Fla., for Raul Charbonier and Luis Charbonier.

John L. Briggs, U.S. Atty., Jacksonville, Fla., Claude H. Tison, Jr., Asst. U.S. Atty., Tampa, Fla., for the United States.

Before WISDOM, AINSWORTH and GEE, Circuit Judges.

GEE, Circuit Judge:

1On appeal from their conviction for various gambling and extortion offenses, appellants raise issues of sufficiency of the evidence, admission of inadmissible hearsay, denial of the right to confrontation, failure to sever the trial of Burke, Hill and Lopez from the trial of Raul and Luis Charbonier, prosecutorial misconduct, improper jury instructions, and collateral estoppel. Concluding that their contentions are meritless, we affirm the convictions.

2In November, 1970, the United States indicted James Burke, Henry Hill, Louis Lopez, Raul Charbonier and Luis Charbonier1 on five counts. The charges consisted of (1) making extortionate extensions of credit;2 using extortionate means of collecting debts;3 (3) interstate travel in furtherance of extortion; (4) interstate travel for promotion of an illegal gambling enterprise; and (5) use of interstate telephone facilities in an unlawful gambling enterprise.4

3The scheme that led to the indictments was crude but effective. Raul Charbonier owned the Char-Pal, a combination lounge-liquor store in Tampa, Florida. His friend Gaspar Ciaccio also owned and operated, in conjunction with his brother Fano Ciaccio, a lounge-liquor store, the Temple Terrace Lounge, located not far from Charbonier's establishment. Early in 1970, Raul Charbonier approached Gaspar Ciaccio with a gambling proposition. Raul could obtain a rigged line or odds sheet on baseball games during the upcoming season from his cousin Pupi in New York, and he offered Ciaccio the opportunity to bet on the games using the line. Gaspar Ciaccio informed his friend Dr. Felix LoCicero of the opportunity and introduced him to Charbonier. In June, 1970, after Charbonier explained the scheme in detail to Ciaccio and LoCicero and enlisted them, they began betting. Charbonier guaranteed that the line was rigged so Ciaccio and Dr. LoCicero would win. The system allowed only bets on the team designated as the favorite in any particular game, at the odds specified. The gamblers could select any number of games on the list to bet on. Charbonier received the line by telephone from New York and phoned the daily lists to either Ciaccio or LoCicero.

4The betting began with bush-league sums in early June, 1970. As promised, Ciaccio and LoCicero won consistently in the beginning, and they increased the amounts of their bets as the season progressed. By the All-Star game break in July, they had compiled $7,500-$8,000 in unpaid winnings. The wagers by that time had reached the major leagues-- as much as $1,000 per game. The All-Star game marked the end of Ciaccio's and LoCicero's hitting streak. After winning the bet on that game, they began striking out consistently. By early August, both had not only lost their previously-compiled winnings but were deeply in the hole. Although they had paid over $7,800, Ciaccio and LoCicero still owed over $13,000 when they called the game. When a friend of Ciaccio's Tony Marchese (who was a bit more knowledgeable about gambling and baseball) saw one of the odds sheets Charbonier supplied Ciaccio, he informed Ciaccio, that, contrary to Charbonier's promise of a line rigged to win, the odds were deceptively rigged to insure losing lets. Ciaccio and LoCicero informed Charbonier that they refused to play and longer.

5LoCicero paid Charbonier another $1,000 on August 24 and had no further contact with him until October 8. The Charboniers did not forget Ciaccio. Raul Charbonier pressed Ciaccio to pay his remaining losses several times between August and October. Ciaccio refused to pay the amount because he believed he had been duped. Once Charbonier assured Ciaccio that, if he did not pay the debt, Charbonier's cousin would come down from New York and 'he would bring some people down there and get the money one way or another.' Raul added to his lineup about that time by substituting his brother Luis as a pinch-hitter. In later August, Luis demanded that Ciaccio pay up. Ciaccio again refused.

6To complete the lineup, Cosmo Rosado, James Burke, Henry Hill and Louis Lopez flew from New York to Tampa the night of October 8 arriving about 9:45 p.m. Rosado rented a car and informed the rental agent that he would use the car for an indeterminate time up to five days without a local address.

7Around 10:30 that night, Luis Charbonier and Rosado, accompanied by the others from New York, accosted Ciaccio in his own lounge. After some serious haggling about Ciaccio's debt, Luis Charbonier and Rosado told Ciaccio to accompany them to Charbonier's lounge. When Ciaccio refused, Burke nudged a gun against his ribs. Having thus received an offer he couldn't refuse, Ciaccio went along, surrounded by the five antagonists. Foregoing any further pleasantries, Hill and Lopez, sitting on either side of Ciaccio in the back seat of the car on the way to the other lounge, began beating him. Lopez split open Ciaccio's forehead with a pistol. Hill and Lopez stated that they would kill Ciaccio, but that it would not be worth-while since they wanted their $8,000.

8Raul Charbonier greeted Ciaccio, when they arrived at the Char-Pal, with, 'I told you this was going to happen to you, didn't I? I told you this.' At the Char-Pal the collector placed Ciaccio in the stockroom and beat on him some more. While Gaspar Ciaccio was enduring his status of punching bag, Raul Carbonier called Gaspar's brother, Fano Ciaccio, at the Temple Terrace Lounge. Raul explained to Fano that they had his brother and they were 'working him over.' Raul said, 'These fellows are from up North and they want their $8,000.' Fano went to the Char-Pal Lounge to negotiate with Charbonier. After Fano explained he did not have the $8,000, Rosado told him that he could have a week to produce it. Subsequently, Raul Charbonier brought Gaspar back to the Temple Terrace Lounge. Some friends helped Gaspar change his bloody clothes and took him to a nearby hospital, where he was treated and the wound in his forehead was stitched up. Gaspar Ciaccio, who was away from work for a week after the beating, borrowed $8,000 from relatives and paid it to Charbonier by the end of the week.

9Raul Charbonier had not forgotten LoCicero either. About midnight on the same night as Ciaccio's beating, Charbonier called LoCicero. Charbonier informed LoCicero that they had Gaspar, they had gasoline in the car, and they wanted to come over to see LoCicero. Charbonier agreed that, if LoCicero would promise to pay the balance in the morning, he would keep them away from him. LoCicero agreed. He offered a thumbnail sketch of his reaction: 'I was scared as hell.' At the earliest opportunity, he paid Raul Charbonier $4,000 to cancel the gambling debt.

10Early on October 9, Rosado turned in the rental car at the airport. Rosado, Burke, Hill and Lopez returned to New York that same morning, flying through Miami.

11On November 24, 1970, six days after the federal indictment was returned, state officials charged these defendants with kidnapping, extortion and assault with intent to murder Gaspar Ciaccio. The state case proceeded expeditiously and was tried in early March, 1971. All defendants were acquitted. The federal case was delayed by various legal maneuverings of the defendants until October, 1972. The trial court directed a verdict of not guilty on Count V as to Burke, Hill and Lopez, because no evidence of phone calls by them existed. The jury found the Charboniers guilty on all counts and Burke, Hill and Lopez guilty on Counts I through IV. The court sentenced each individual to ten years' imprisonment.

Evidentiary Issues

12Burke, Hill and Lopez contend pro forma that the evidence was insufficient to sustain their convictions. The contention is frivolous in light of the overwhelming and detailed testimony by Ciaccio and others about these appellants' conduct. But Burke, Hill and Lopez seriously insist that massive infusions of inadmissible hearsay denied them a fair trial and their respective rights to confront the witnesses against them.5

13First, they complain of Ciaccio's and LoCicero's testimony about the operation of the gambling scheme during the spring and summer. They assert as inadmissible hearsay virtually everything the witnesses said that Raul Charbonier said or did. These statements, rather than hearsay, as appellants assert, were 'berbal acts,' statements which were elements of the crimes charged. With the exceptions discussed below, none of the statements or acts attributed to Charbonier referred to Burke, Hill and Lopez.

14Henry Hill Sports Betting

The issue, then, is whether this non-hearsay evidence was admissible in the trial against Burke, Hill and Lopez. Doubtless it was relevant. It established and detailed the gambling scheme which was the context for the extortionate extensions of credit and the extortionate collection methods. Additionally, the gambling supplied the element which made the interstate travel and use of interstate telephone facilities illegal. No issue of prejudice or necessity for cautionary instructions arose because these defendants were not mentioned as involved in the original arrangements or operations of the gambling scheme. Whether these particular acts of Charbonier were attributable to Burke, Hill and Lopez was essentially irrelevant. As to them, it was only the action of October 8th to which federal criminal liability could be ascribed. To the extent the jury may have associated these defendants with the origination of the gambling, it was permissible under the traditional principle that the acts of one partner in crime are admissible against the others when it is in furtherance of the criminal undertaking. Orser v. United States, 362F.2d580, 585 (5th Cir. 1966).

15The witnesses did relate a few statements by the Charboniers referring to Cosmo Rosado, the 'cousin from up North' and to 'people' that his cousin would 'bring down here and get the money one way or another.' Most clearly incriminating to these three appellants was the phone conversation between Raul Charbonier and LoCicero of October 8th, related by LoCicero on the witness stand:

16I received a telephone call and the words were, 'Doc, this is Raul. They have Gaspar in the car. They have gasoline in the car. And they want to come over to see you. If you guaranty me you will pay the balance by tomorrow I will tell them not to come over.'

17I related at that time that I thought that matter had been settled. Says, 'No. They want their money now.' Says, 'Well you come to my office tomorrow and I will have the money for you.' He said, 'That is good enough for me.' And hung up.

Again, these statements were not hearsay but were statements which constituted the very activity in combination with which the defendants were charged. As such, they were admissible and attributable to Burke, Hill and Lopez. Additionally, these statements did not deny these appellants the Sixth Amendment right to confront the witnesses against them. Although the rationale for admission of these statements is not the co-conspirator exception to the hearsay rule,6 the analysis of these 'verbal acts' in light of the confrontation clause necessarily follows many of the same guidelines. The declarants, as defendants, were unavailable to the government; sufficient indicia of reliability, both as to Charbonier's thereatening purpose and as to the reference on October 8th to 'they,' meaning Burke, Hill and Lopez,7 was supplied by overwhelming independent evidence of these appellants' activities; also, in light of the direct evidence of Burke's, Hill's and Lopez' participation, references to 'they' were not 'crucial' to the government's case nor 'devastating' to the defense. Dutton v. Evans, 400U.S.74, 91S. Ct.210, 27L. Ed. 2d213(1970); Park v. Huff, 493F.2d923(5th Cir. 1974); Davenport, The Confrontation Clause and the Co-conspirator Exception in Criminal Prosecutions: A Functional Analysis, 85 Harv.L.Rev. 1378 (1972).

19Appellants insist not only that the evidence was inadmissible but that they were prejudicially misled by a preliminary statement that the conspiracy rules of evidence were not applicable and by the failure of the prosecution to define the scope and purpose of any conspiracy or joint venture in crime. We find no evidence in the record of disadvantage or prejudice to appellants. They were afforded full opportunity to present their objections, which they did-- promptly, thoroughly and unctuously. The trial judge, at an appropriate time, found that sufficient independent evidence of the 'co-partnership,' 'joint venture,' or common undertaking of a criminal objective existed to establish that relationship between defendants, to reinforce the reliability of the extra-judicial statements, and to furnish the necessary relevance of the evidence. Orser v. United States, supra, at 585.

20

Two more minor evidentiary questions warrant discussion. First, appellants insist that Gaspar Ciaccio's testimony about his statements to his treating doctor on the night of October 8th after his beating were inadmissible hearsay. Assuming appellants are correct that the statements about his beating were not necessary for medical diagnosis or treatment, the testimony was still admissible to support Ciaccio's story after the defense had attacked Ciaccio's story as a recent fabrication. McCormick, Evidence (2d) 251 (1972). Secondly, appellants claim that the testimony of a government agent relating an interview with Raul Charbonier on November 13, 1970, was inadmissible. We agree that it was inadmissible simply as irrelevant, if for no other reason. During the interview, Charbonier denied the whole gambling and extortion scheme. Additionally, it was not in furtherance of the criminal goal for which defendants were charged. And it lacked any reference to any other defendant. Whatever effect the statement may have generated, however, it was not substantial or prejudicial enough to warrant reversal.

21Earl Cram, a witness, had seen Gaspar Ciaccio come out of his lounge on October 8th surrounded by four of the defendants and Rosado. After cross-examination of Cram, defendants sought to show his bias by introducing statements by Cram, after defendants' acquittal in state court, that he was unhappy with, and skeptical of, that trial's outcome. Defendants did not show material differences from the state trial in Cram's testimony or any other way in which his testimony was biased by the state trial outcome. Additionally, the district court had earlier ruled that evidence of the state acquittal was irrelevant and it was within his discretion to foreclose the defendants' attempt to refer to it.

22Direct examination of Gaspar Ciaccio lasted until late on a Friday afternoon before a three-day weekend. The district Judge granted permission for the prosecutor to 'work with' Ciaccio over the weekend in order to discuss the upcoming cross-examination. Defendants urge that this deprived them of the 'timely thrust of naturalness' inherently essential to cross-examination. The defense had the full weekend to prepare its cross-examination and they have not shown any prejudice resulting from the two-hour conference between Ciaccio and the prosecutor. Thus, we cannot say the district court abused its discretion in allowing it.

Severance

23Appellants insist that the district court erred in failing to grant a severance of the Charboniers' trial from that of Burke, Hill and Lopez. Rule 14, F.R.Crim.P., provides that a motion for a severance is addressed to the discretion of the trial judge. Opper v. United States, 348U.S.84, 75S. Ct.158, 99L. Ed.101(1954); Smith v. United States, 385F.2d34(5th Cir. 1967). To challenge successfully the refusal of a trial judge to grant a motion to sever, an appellant must show 'prejudice resulting in the denial of a fair trial.' United States v. Martinez, 486F.2d15(5th Cir. 1973); United States v. Nakaladski, 481F.2d289(5th Cir. 1973). In Byrd v. Wainwright, 428F.2d1017(5th Cir. 1970), we enumerated guidelines for evaluating motions for severance based on a desire to offer exculpatory testimony of a co-defendant.8

24We agree that the defendants satisfied two of the criteria. (1) Burke, Hill and Lopez subpoenaed the Charboniers as witnesses and, although tardily, sufficiently communicated to the trial judge that they desired to use the Charboniers as witnesses; (2) the appellants timely made (although over a year after indictment) the requisite motions and renewed them during trial.

25On the other hand, we cannot say that these appellants satisfied the other criteria sufficiently to warrant a conclusion that the district court abused its discretion. (1) The Charboniers filed affidavits which tracked exactly the language of the indictments but expressed it in the negative. These affidavits failed to clearly show what the Charboniers would have testified to. The movants made no showing that the Charboniers' testimony would be exculpatory in effect or would raise strong doubts as to Burke's, Hill's and Lopez' guilt. Byrd, supra at 1020-1021. (2) The likelihood that the Charboniers would testify if tried separately was enhanced by the Charboniers' affidavits to that effect, but that likelihood was diminished by the failure to show why the Charboniers would have been willing to testify at a separate trial but not in the joint one. The usual reason for such a strategy is inconsistent or antagonistic defenses-- the testimony that exonerates the movant will implicate the co-defendant witness. Byrd, supra at 1022; United States v. Johnson, 478F.2d1129(5th Cir. 1973). Appellants made no such showing to the trial judge. (3) Considerations weigh heavily in favor of the district court's decision. By various district court's decision. By various manuevers defendants delayed commencement of the trial for almost two years after indictment, the trial itself required nearly three weeks, and separate trials would have required virtual duplication of great effort and expense.

Miscellaneous

26Appellants urge that the following remark by the prosecutor during rebuttal argument was improper comment on the failure of the defendants to take the stand:

27Defense counsel stated that, while they were not there and I wasn't there-- I want to point out to you, ladies and gentlemen, that the people who were there were all the witnesses who testified to the facts and all of the defendants, and they were there when this occurred; and you have the testimony as to what happened.

28In the context presented, countervailing arguments by counsel that neither the prosecutor's nor the defense counsel's statements constitute evidence in the case, we cannot conclude that this statement '. . . was manifestly intended or was 'of such a character that the jury would naturally and necessarily take it to be a comment on the failure of the accused to testify.' United States v. White, 444F.2d1274, 1278 (5th Cir. 1971).

29Appellants also insist that the prosecutor below engaged in other serious misconduct sufficient to deny them a fair trial. After reviewing the record of the incidents, statements and arguments alleged to have been prejudicial, we conclude that they were not so misleading, inflammatory or prejudicial as to deny defendants a fair trial.

30In the state trial, Fano Ciaccio had denied that he knew of his brother's gambling. At the federal trial, he acknowledged that his earlier statement was false and explained that he had been afraid at the time to expose his knowledge of the gambling because of the treatment received by his brother. Additionally, due to language difficulties Fano was confused and made misstatements on cross-examination which he or the prosecutor had to correct. On these factors, defense counsel requested the district judge to specially instruct the jury about admitted perjurious testimony. and to apply the maxim 'falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus' to Fano's testimony. The trial judge refused to so instruct the jury, but he allowed defense counsel to argue the point to the jury. In light of all the circumstances and the thorough instructions given by the court, we cannot conclude the failure to give these instructions was error. Cf. Luna v. Beto, 395F.2d35(5th Cir. 1968).

31Finally, appellants' contention that the federal government was precluded by doctrines of double jeopardy and collateral estoppel from trying these defendants under these charges after the state court acquitted them is foreclosed by Bartkus v. Illinois, 359U.S.121, 79S. Ct.676, 3L. Ed. 2d684(1959), and Abbate v. United States, 359U.S.187, 79S. Ct.666, 3L. Ed. 2d729(1959); see United States v. Vaughan, 491F.2d1096(5th Cir. 1974).

1Cosmo Rosado ('Pupi'), the Charboniers' cousin, was indicted also, but he died shortly before trial

892Making extortionate extensions of credit

(a) Whoever makes any extortionate extension of credit, or conspires to do so, shall be fined not more than $10,000 or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

(b) In any prosecution under this section, if it is shown that all of the following factors were present in connection with the extension of credit in question, there is prima facie evidence that the extension of credit was extortionate, but this subsection is nonexclusive and in no way limits the effect or applicability of subsection (a):

(1) The repayment of the extension of credit, or the performance of any promise given in consideration thereof, would be unenforceable, through civil judicial processes against the debtor

(A) in the jurisdiction within which the debtor, if a natural person, resided or

(B) in every jurisdiction within which the debtor, if other than a natural person, was incorporated or qualified to do business at the time the extension of credit was made.

(2) The extention of credit was made at a rate of interest in excess of an annual rate of 45 per centum calculated according to the actuarial method of allocating payments made on a debt between principal and interest, pursuant to which a payment in applied first to the accumulated interest and the balance is applied to the unpaid principal.

(3) At the time the extension of credit was made, the debtor reasonably believed that either

(A) one or more extensions of credit by the creditor had been collected or attempted to be collected by extortionate means, or the nonrepayment thereof had been punished by extortionate means; or

(B) the creditor had a reputation for the use of extortionate means to collect extensions of credit or to punish the nonrepayment thereof.

(4) Upon the making of the extension of credit, the total of the extensions of credit by the creditor to the debtor then outstanding, including any unpaid interest or similar charges, exceeded $100.

(c) In any prosecution under this section, if evidence has been introduced tending to show the existence of any of the circumstances described in subsection (b)(1) or (b)(2), and direct evidence of the actual belief of the debtor as to the creditor's collection practices is not available, then for the purpose of showing the understanding of the debtor and the creditor at the time the extension of credit was made, the court may in its discretion allow evidence to be introduced tending to show the reputation as to collection practices of the creditor in any community of which the debtor was a member at the time of the extension.

894Collection of extensions of credit by extortionate means

(a) Whoever knowingly participates in any way, or conspires to do so, in the use of any extortionate means

(1) to collect or attempt to collect any extension of credit, or

(2) to punish any person for the nonrepayment thereof,

shall be fined not more than $10,000 or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

(b) In any prosecution under this section for the purpose of showing an implicit threat as a means of collection, evidence may be introduced tending to show that one or more extensions of credit by the creditor were, to the knowledge of the person against whom the implicit threat was alleged to have been made, collected or attempted to be collected by extortionate means or that the nonrepayment thereof was punishment by extortionate means.

(c) In any prosecution under this section, if evidence has been introduced tending to show the existence, at the time the extension of credit in question was made, of the circumstances described in section 892(b)(1) or the circumstances described in section 892(b)(2), and direct evidence of the actual belief of the debtor as to the creditor's collection practices is not available, then for the purpose of showing that words or other means of communication, shown to have been employed as a means of collection, in fact carried an express or implicit threat, the court may in its discretion allow evidence to be introduced tending to show the reputation of the defendant in any community of which the person against whom the alleged threat was made was a member at the time of the collection or attempt at collection.

4The last three counts in violation of 18 U.S.C.A. 1952:

1952. Interstate and foreign travel or transportation in aid of racketeering enterprises

(a) Whoever travels in interstate or foreign commerce or uses any facility in interstate or foreign commerce, including the mail, with intent to--

Barry A. Cohen, Paul Antinori, Tampa, Fla., for James Burke et al.

Raymond E. LaPorte, Tampa, Fla., for Raul Charbonier and Luis Charbonier.

John L. Briggs, U.S. Atty., Jacksonville, Fla., Claude H. Tison, Jr., Asst. U.S. Atty., Tampa, Fla., for the United States.

Before WISDOM, AINSWORTH and GEE, Circuit Judges.

GEE, Circuit Judge:

1On appeal from their conviction for various gambling and extortion offenses, appellants raise issues of sufficiency of the evidence, admission of inadmissible hearsay, denial of the right to confrontation, failure to sever the trial of Burke, Hill and Lopez from the trial of Raul and Luis Charbonier, prosecutorial misconduct, improper jury instructions, and collateral estoppel. Concluding that their contentions are meritless, we affirm the convictions.

2In November, 1970, the United States indicted James Burke, Henry Hill, Louis Lopez, Raul Charbonier and Luis Charbonier1 on five counts. The charges consisted of (1) making extortionate extensions of credit;2 using extortionate means of collecting debts;3 (3) interstate travel in furtherance of extortion; (4) interstate travel for promotion of an illegal gambling enterprise; and (5) use of interstate telephone facilities in an unlawful gambling enterprise.4

3The scheme that led to the indictments was crude but effective. Raul Charbonier owned the Char-Pal, a combination lounge-liquor store in Tampa, Florida. His friend Gaspar Ciaccio also owned and operated, in conjunction with his brother Fano Ciaccio, a lounge-liquor store, the Temple Terrace Lounge, located not far from Charbonier's establishment. Early in 1970, Raul Charbonier approached Gaspar Ciaccio with a gambling proposition. Raul could obtain a rigged line or odds sheet on baseball games during the upcoming season from his cousin Pupi in New York, and he offered Ciaccio the opportunity to bet on the games using the line. Gaspar Ciaccio informed his friend Dr. Felix LoCicero of the opportunity and introduced him to Charbonier. In June, 1970, after Charbonier explained the scheme in detail to Ciaccio and LoCicero and enlisted them, they began betting. Charbonier guaranteed that the line was rigged so Ciaccio and Dr. LoCicero would win. The system allowed only bets on the team designated as the favorite in any particular game, at the odds specified. The gamblers could select any number of games on the list to bet on. Charbonier received the line by telephone from New York and phoned the daily lists to either Ciaccio or LoCicero.

4The betting began with bush-league sums in early June, 1970. As promised, Ciaccio and LoCicero won consistently in the beginning, and they increased the amounts of their bets as the season progressed. By the All-Star game break in July, they had compiled $7,500-$8,000 in unpaid winnings. The wagers by that time had reached the major leagues-- as much as $1,000 per game. The All-Star game marked the end of Ciaccio's and LoCicero's hitting streak. After winning the bet on that game, they began striking out consistently. By early August, both had not only lost their previously-compiled winnings but were deeply in the hole. Although they had paid over $7,800, Ciaccio and LoCicero still owed over $13,000 when they called the game. When a friend of Ciaccio's Tony Marchese (who was a bit more knowledgeable about gambling and baseball) saw one of the odds sheets Charbonier supplied Ciaccio, he informed Ciaccio, that, contrary to Charbonier's promise of a line rigged to win, the odds were deceptively rigged to insure losing lets. Ciaccio and LoCicero informed Charbonier that they refused to play and longer.

5LoCicero paid Charbonier another $1,000 on August 24 and had no further contact with him until October 8. The Charboniers did not forget Ciaccio. Raul Charbonier pressed Ciaccio to pay his remaining losses several times between August and October. Ciaccio refused to pay the amount because he believed he had been duped. Once Charbonier assured Ciaccio that, if he did not pay the debt, Charbonier's cousin would come down from New York and 'he would bring some people down there and get the money one way or another.' Raul added to his lineup about that time by substituting his brother Luis as a pinch-hitter. In later August, Luis demanded that Ciaccio pay up. Ciaccio again refused.

6To complete the lineup, Cosmo Rosado, James Burke, Henry Hill and Louis Lopez flew from New York to Tampa the night of October 8 arriving about 9:45 p.m. Rosado rented a car and informed the rental agent that he would use the car for an indeterminate time up to five days without a local address.

7Around 10:30 that night, Luis Charbonier and Rosado, accompanied by the others from New York, accosted Ciaccio in his own lounge. After some serious haggling about Ciaccio's debt, Luis Charbonier and Rosado told Ciaccio to accompany them to Charbonier's lounge. When Ciaccio refused, Burke nudged a gun against his ribs. Having thus received an offer he couldn't refuse, Ciaccio went along, surrounded by the five antagonists. Foregoing any further pleasantries, Hill and Lopez, sitting on either side of Ciaccio in the back seat of the car on the way to the other lounge, began beating him. Lopez split open Ciaccio's forehead with a pistol. Hill and Lopez stated that they would kill Ciaccio, but that it would not be worth-while since they wanted their $8,000.

8Raul Charbonier greeted Ciaccio, when they arrived at the Char-Pal, with, 'I told you this was going to happen to you, didn't I? I told you this.' At the Char-Pal the collector placed Ciaccio in the stockroom and beat on him some more. While Gaspar Ciaccio was enduring his status of punching bag, Raul Carbonier called Gaspar's brother, Fano Ciaccio, at the Temple Terrace Lounge. Raul explained to Fano that they had his brother and they were 'working him over.' Raul said, 'These fellows are from up North and they want their $8,000.' Fano went to the Char-Pal Lounge to negotiate with Charbonier. After Fano explained he did not have the $8,000, Rosado told him that he could have a week to produce it. Subsequently, Raul Charbonier brought Gaspar back to the Temple Terrace Lounge. Some friends helped Gaspar change his bloody clothes and took him to a nearby hospital, where he was treated and the wound in his forehead was stitched up. Gaspar Ciaccio, who was away from work for a week after the beating, borrowed $8,000 from relatives and paid it to Charbonier by the end of the week.

9Raul Charbonier had not forgotten LoCicero either. About midnight on the same night as Ciaccio's beating, Charbonier called LoCicero. Charbonier informed LoCicero that they had Gaspar, they had gasoline in the car, and they wanted to come over to see LoCicero. Charbonier agreed that, if LoCicero would promise to pay the balance in the morning, he would keep them away from him. LoCicero agreed. He offered a thumbnail sketch of his reaction: 'I was scared as hell.' At the earliest opportunity, he paid Raul Charbonier $4,000 to cancel the gambling debt.

10Early on October 9, Rosado turned in the rental car at the airport. Rosado, Burke, Hill and Lopez returned to New York that same morning, flying through Miami.

11On November 24, 1970, six days after the federal indictment was returned, state officials charged these defendants with kidnapping, extortion and assault with intent to murder Gaspar Ciaccio. The state case proceeded expeditiously and was tried in early March, 1971. All defendants were acquitted. The federal case was delayed by various legal maneuverings of the defendants until October, 1972. The trial court directed a verdict of not guilty on Count V as to Burke, Hill and Lopez, because no evidence of phone calls by them existed. The jury found the Charboniers guilty on all counts and Burke, Hill and Lopez guilty on Counts I through IV. The court sentenced each individual to ten years' imprisonment.

Evidentiary Issues

12Burke, Hill and Lopez contend pro forma that the evidence was insufficient to sustain their convictions. The contention is frivolous in light of the overwhelming and detailed testimony by Ciaccio and others about these appellants' conduct. But Burke, Hill and Lopez seriously insist that massive infusions of inadmissible hearsay denied them a fair trial and their respective rights to confront the witnesses against them.5

13First, they complain of Ciaccio's and LoCicero's testimony about the operation of the gambling scheme during the spring and summer. They assert as inadmissible hearsay virtually everything the witnesses said that Raul Charbonier said or did. These statements, rather than hearsay, as appellants assert, were 'berbal acts,' statements which were elements of the crimes charged. With the exceptions discussed below, none of the statements or acts attributed to Charbonier referred to Burke, Hill and Lopez.

14Henry Hill Sports Betting

The issue, then, is whether this non-hearsay evidence was admissible in the trial against Burke, Hill and Lopez. Doubtless it was relevant. It established and detailed the gambling scheme which was the context for the extortionate extensions of credit and the extortionate collection methods. Additionally, the gambling supplied the element which made the interstate travel and use of interstate telephone facilities illegal. No issue of prejudice or necessity for cautionary instructions arose because these defendants were not mentioned as involved in the original arrangements or operations of the gambling scheme. Whether these particular acts of Charbonier were attributable to Burke, Hill and Lopez was essentially irrelevant. As to them, it was only the action of October 8th to which federal criminal liability could be ascribed. To the extent the jury may have associated these defendants with the origination of the gambling, it was permissible under the traditional principle that the acts of one partner in crime are admissible against the others when it is in furtherance of the criminal undertaking. Orser v. United States, 362F.2d580, 585 (5th Cir. 1966).

15The witnesses did relate a few statements by the Charboniers referring to Cosmo Rosado, the 'cousin from up North' and to 'people' that his cousin would 'bring down here and get the money one way or another.' Most clearly incriminating to these three appellants was the phone conversation between Raul Charbonier and LoCicero of October 8th, related by LoCicero on the witness stand:

16I received a telephone call and the words were, 'Doc, this is Raul. They have Gaspar in the car. They have gasoline in the car. And they want to come over to see you. If you guaranty me you will pay the balance by tomorrow I will tell them not to come over.'

17I related at that time that I thought that matter had been settled. Says, 'No. They want their money now.' Says, 'Well you come to my office tomorrow and I will have the money for you.' He said, 'That is good enough for me.' And hung up.

18Again, these statements were not hearsay but were statements which constituted the very activity in combination with which the defendants were charged. As such, they were admissible and attributable to Burke, Hill and Lopez. Additionally, these statements did not deny these appellants the Sixth Amendment right to confront the witnesses against them. Although the rationale for admission of these statements is not the co-conspirator exception to the hearsay rule,6 the analysis of these 'verbal acts' in light of the confrontation clause necessarily follows many of the same guidelines. The declarants, as defendants, were unavailable to the government; sufficient indicia of reliability, both as to Charbonier's thereatening purpose and as to the reference on October 8th to 'they,' meaning Burke, Hill and Lopez,7 was supplied by overwhelming independent evidence of these appellants' activities; also, in light of the direct evidence of Burke's, Hill's and Lopez' participation, references to 'they' were not 'crucial' to the government's case nor 'devastating' to the defense. Dutton v. Evans, 400U.S.74, 91S. Ct.210, 27L. Ed. 2d213(1970); Park v. Huff, 493F.2d923(5th Cir. 1974); Davenport, The Confrontation Clause and the Co-conspirator Exception in Criminal Prosecutions: A Functional Analysis, 85 Harv.L.Rev. 1378 (1972).

19Appellants insist not only that the evidence was inadmissible but that they were prejudicially misled by a preliminary statement that the conspiracy rules of evidence were not applicable and by the failure of the prosecution to define the scope and purpose of any conspiracy or joint venture in crime. We find no evidence in the record of disadvantage or prejudice to appellants. They were afforded full opportunity to present their objections, which they did-- promptly, thoroughly and unctuously. The trial judge, at an appropriate time, found that sufficient independent evidence of the 'co-partnership,' 'joint venture,' or common undertaking of a criminal objective existed to establish that relationship between defendants, to reinforce the reliability of the extra-judicial statements, and to furnish the necessary relevance of the evidence. Orser v. United States, supra, at 585.

20Two more minor evidentiary questions warrant discussion. First, appellants insist that Gaspar Ciaccio's testimony about his statements to his treating doctor on the night of October 8th after his beating were inadmissible hearsay. Assuming appellants are correct that the statements about his beating were not necessary for medical diagnosis or treatment, the testimony was still admissible to support Ciaccio's story after the defense had attacked Ciaccio's story as a recent fabrication. McCormick, Evidence (2d) 251 (1972). Secondly, appellants claim that the testimony of a government agent relating an interview with Raul Charbonier on November 13, 1970, was inadmissible. We agree that it was inadmissible simply as irrelevant, if for no other reason. During the interview, Charbonier denied the whole gambling and extortion scheme. Additionally, it was not in furtherance of the criminal goal for which defendants were charged. And it lacked any reference to any other defendant. Whatever effect the statement may have generated, however, it was not substantial or prejudicial enough to warrant reversal.

21Earl Cram, a witness, had seen Gaspar Ciaccio come out of his lounge on October 8th surrounded by four of the defendants and Rosado. After cross-examination of Cram, defendants sought to show his bias by introducing statements by Cram, after defendants' acquittal in state court, that he was unhappy with, and skeptical of, that trial's outcome. Defendants did not show material differences from the state trial in Cram's testimony or any other way in which his testimony was biased by the state trial outcome. Additionally, the district court had earlier ruled that evidence of the state acquittal was irrelevant and it was within his discretion to foreclose the defendants' attempt to refer to it.

22Direct examination of Gaspar Ciaccio lasted until late on a Friday afternoon before a three-day weekend. The district Judge granted permission for the prosecutor to 'work with' Ciaccio over the weekend in order to discuss the upcoming cross-examination. Defendants urge that this deprived them of the 'timely thrust of naturalness' inherently essential to cross-examination. The defense had the full weekend to prepare its cross-examination and they have not shown any prejudice resulting from the two-hour conference between Ciaccio and the prosecutor. Thus, we cannot say the district court abused its discretion in allowing it.

Severance

23Appellants insist that the district court erred in failing to grant a severance of the Charboniers' trial from that of Burke, Hill and Lopez. Rule 14, F.R.Crim.P., provides that a motion for a severance is addressed to the discretion of the trial judge. Opper v. United States, 348U.S.84, 75S. Ct.158, 99L. Ed.101(1954); Smith v. United States, 385F.2d34(5th Cir. 1967). To challenge successfully the refusal of a trial judge to grant a motion to sever, an appellant must show 'prejudice resulting in the denial of a fair trial.' United States v. Martinez, 486F.2d15(5th Cir. 1973); United States v. Nakaladski, 481F.2d289(5th Cir. 1973). In Byrd v. Wainwright, 428F.2d1017(5th Cir. 1970), we enumerated guidelines for evaluating motions for severance based on a desire to offer exculpatory testimony of a co-defendant.8

24We agree that the defendants satisfied two of the criteria. (1) Burke, Hill and Lopez subpoenaed the Charboniers as witnesses and, although tardily, sufficiently communicated to the trial judge that they desired to use the Charboniers as witnesses; (2) the appellants timely made (although over a year after indictment) the requisite motions and renewed them during trial.

25On the other hand, we cannot say that these appellants satisfied the other criteria sufficiently to warrant a conclusion that the district court abused its discretion. (1) The Charboniers filed affidavits which tracked exactly the language of the indictments but expressed it in the negative. These affidavits failed to clearly show what the Charboniers would have testified to. The movants made no showing that the Charboniers' testimony would be exculpatory in effect or would raise strong doubts as to Burke's, Hill's and Lopez' guilt. Byrd, supra at 1020-1021. (2) The likelihood that the Charboniers would testify if tried separately was enhanced by the Charboniers' affidavits to that effect, but that likelihood was diminished by the failure to show why the Charboniers would have been willing to testify at a separate trial but not in the joint one. The usual reason for such a strategy is inconsistent or antagonistic defenses-- the testimony that exonerates the movant will implicate the co-defendant witness. Byrd, supra at 1022; United States v. Johnson, 478F.2d1129(5th Cir. 1973). Appellants made no such showing to the trial judge. (3) Considerations weigh heavily in favor of the district court's decision. By various district court's decision. By various manuevers defendants delayed commencement of the trial for almost two years after indictment, the trial itself required nearly three weeks, and separate trials would have required virtual duplication of great effort and expense.

Miscellaneous

26Appellants urge that the following remark by the prosecutor during rebuttal argument was improper comment on the failure of the defendants to take the stand:

27Defense counsel stated that, while they were not there and I wasn't there-- I want to point out to you, ladies and gentlemen, that the people who were there were all the witnesses who testified to the facts and all of the defendants, and they were there when this occurred; and you have the testimony as to what happened.

28In the context presented, countervailing arguments by counsel that neither the prosecutor's nor the defense counsel's statements constitute evidence in the case, we cannot conclude that this statement '. . . was manifestly intended or was 'of such a character that the jury would naturally and necessarily take it to be a comment on the failure of the accused to testify.' United States v. White, 444F.2d1274, 1278 (5th Cir. 1971).

29Appellants also insist that the prosecutor below engaged in other serious misconduct sufficient to deny them a fair trial. After reviewing the record of the incidents, statements and arguments alleged to have been prejudicial, we conclude that they were not so misleading, inflammatory or prejudicial as to deny defendants a fair trial.

30In the state trial, Fano Ciaccio had denied that he knew of his brother's gambling. At the federal trial, he acknowledged that his earlier statement was false and explained that he had been afraid at the time to expose his knowledge of the gambling because of the treatment received by his brother. Additionally, due to language difficulties Fano was confused and made misstatements on cross-examination which he or the prosecutor had to correct. On these factors, defense counsel requested the district judge to specially instruct the jury about admitted perjurious testimony. and to apply the maxim 'falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus' to Fano's testimony. The trial judge refused to so instruct the jury, but he allowed defense counsel to argue the point to the jury. In light of all the circumstances and the thorough instructions given by the court, we cannot conclude the failure to give these instructions was error. Cf. Luna v. Beto, 395F.2d35(5th Cir. 1968).

31Finally, appellants' contention that the federal government was precluded by doctrines of double jeopardy and collateral estoppel from trying these defendants under these charges after the state court acquitted them is foreclosed by Bartkus v. Illinois, 359U.S.121, 79S. Ct.676, 3L. Ed. 2d684(1959), and Abbate v. United States, 359U.S.187, 79S. Ct.666, 3L. Ed. 2d729(1959); see United States v. Vaughan, 491F.2d1096(5th Cir. 1974).

1Cosmo Rosado ('Pupi'), the Charboniers' cousin, was indicted also, but he died shortly before trial

892Making extortionate extensions of credit

(a) Whoever makes any extortionate extension of credit, or conspires to do so, shall be fined not more than $10,000 or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

(b) In any prosecution under this section, if it is shown that all of the following factors were present in connection with the extension of credit in question, there is prima facie evidence that the extension of credit was extortionate, but this subsection is nonexclusive and in no way limits the effect or applicability of subsection (a):

(1) The repayment of the extension of credit, or the performance of any promise given in consideration thereof, would be unenforceable, through civil judicial processes against the debtor

(A) in the jurisdiction within which the debtor, if a natural person, resided or

(B) in every jurisdiction within which the debtor, if other than a natural person, was incorporated or qualified to do business at the time the extension of credit was made.

(2) The extention of credit was made at a rate of interest in excess of an annual rate of 45 per centum calculated according to the actuarial method of allocating payments made on a debt between principal and interest, pursuant to which a payment in applied first to the accumulated interest and the balance is applied to the unpaid principal.

(3) At the time the extension of credit was made, the debtor reasonably believed that either

(A) one or more extensions of credit by the creditor had been collected or attempted to be collected by extortionate means, or the nonrepayment thereof had been punished by extortionate means; or

(B) the creditor had a reputation for the use of extortionate means to collect extensions of credit or to punish the nonrepayment thereof.

(4) Upon the making of the extension of credit, the total of the extensions of credit by the creditor to the debtor then outstanding, including any unpaid interest or similar charges, exceeded $100.

(c) In any prosecution under this section, if evidence has been introduced tending to show the existence of any of the circumstances described in subsection (b)(1) or (b)(2), and direct evidence of the actual belief of the debtor as to the creditor's collection practices is not available, then for the purpose of showing the understanding of the debtor and the creditor at the time the extension of credit was made, the court may in its discretion allow evidence to be introduced tending to show the reputation as to collection practices of the creditor in any community of which the debtor was a member at the time of the extension.

894Collection of extensions of credit by extortionate means

(a) Whoever knowingly participates in any way, or conspires to do so, in the use of any extortionate means

(1) to collect or attempt to collect any extension of credit, or

(2) to punish any person for the nonrepayment thereof,

shall be fined not more than $10,000 or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

(b) In any prosecution under this section for the purpose of showing an implicit threat as a means of collection, evidence may be introduced tending to show that one or more extensions of credit by the creditor were, to the knowledge of the person against whom the implicit threat was alleged to have been made, collected or attempted to be collected by extortionate means or that the nonrepayment thereof was punishment by extortionate means.

(c) In any prosecution under this section, if evidence has been introduced tending to show the existence, at the time the extension of credit in question was made, of the circumstances described in section 892(b)(1) or the circumstances described in section 892(b)(2), and direct evidence of the actual belief of the debtor as to the creditor's collection practices is not available, then for the purpose of showing that words or other means of communication, shown to have been employed as a means of collection, in fact carried an express or implicit threat, the court may in its discretion allow evidence to be introduced tending to show the reputation of the defendant in any community of which the person against whom the alleged threat was made was a member at the time of the collection or attempt at collection.

4The last three counts in violation of 18 U.S.C.A. 1952:

1952. Interstate and foreign travel or transportation in aid of racketeering enterprises

(a) Whoever travels in interstate or foreign commerce or uses any facility in interstate or foreign commerce, including the mail, with intent to--

(1) distribute the proceeds of any unlawful activity; or

(2) commit any crime of violence to further any unlawful activity; or

(3) otherwise promote, manage, establish, carry on, or facilitate the promotion, management, establishment, or carrying on, of any unlawful activity, and thereafter performs or attempts to perform any of the acts specified in subparagraphs (1), (2), and (3), shall be fined not more than $10,000 or imprisoned for not more than five years, or both.

(b) As used in this section 'unlawful activity' means (1) any business enterprise involving gambling, liquor on which the Federal excise tax has not been paid, narcotics or controlled substances (as defined in section 102(6) of the Controlled Substances Act), or prostitution offenses in violation of the laws of the State in which they are committed or of the United States, or (2) extortion, bribery, or arson in violation of the laws of the State in which committed or of the United States.

(c) Investigations of violations under this section involving liquor shall be conducted under the supervision of the Secretary of the Treasury.

5The Charboniers do not brief but simply adopt, where applicable, the arguments of Burke, Hill and Lopez on the issues of inadmissible hearsay, severance and collateral estoppel. Where applicable, we reject the Charboniers' adoption of those arguments. Burke, Hill and Lopez, in turn, do not brief but simply adopt, where applicable, the arguments of the Charboniers on the issues of prosecutional misconduct, improper comment on defendants' failure to testify, denial of confrontation and due process as to witness Cram, and failure of the court to give requested instructions. Where applicable, we reject Burke's, Hill's and Lopez' adoption of those arguments

6Thus we need not consider whether conspiracy must actually be charged in order to invoke that exception. Compare United States v. Harrell, 436F.2d606, 616 (5th Cir. 1970), with United States v. Williamson, 482F.2d508, 513 (5th Cir. 1973)

8See United States v. Martinez, 486F.2d15, 22 (5th Cir. 1973), where we said that the Fourteenth Amendment due process criteria are similar to those of Rule 14, F.R.Crim.P

Mafia are just like the rest of us — especially if you aspire to die by being shot in the head, which happened with alarming frequency in Martin Scorsese's The Irishman and, actually, throughout the annals of organized crime. It's not the only way to go — after getting out of Alcatraz, Capone himself perished as a result of a stroke and heart attack in Florida, but that was after a long slide into mental incapacity from untreated syphilis. Bonnie and Clyde, though not Mafia, took a couple to the head — and just about everywhere else. Jessie James, Butch and Sundance — it's a long American tradition. For criminals, anyway.

So maybe it comes as a surprise that Henry Hill, the gangster who inspired the book Wiseguy and Ray Liotta's performance in Goodfellas (again, Scorsese, not to mention a segment of Animaniacs) didn't die of lead poisoning, so to speak. No; Hill, what his criminal compadres would call a rat, had a much more boring (though perhaps not for him) exit to the choir invisible.

Biography tells us that Hill aspired to hoodlumhood from the age of 12. His problem was that he wasn't 100% Italian — his father was Irish, his mother Sicilian — but that didn't stop him from giving it the good ol' college try. The Luchese crime family ruled Hill's neighborhood and Hill became involved in gambling and the drug trade.

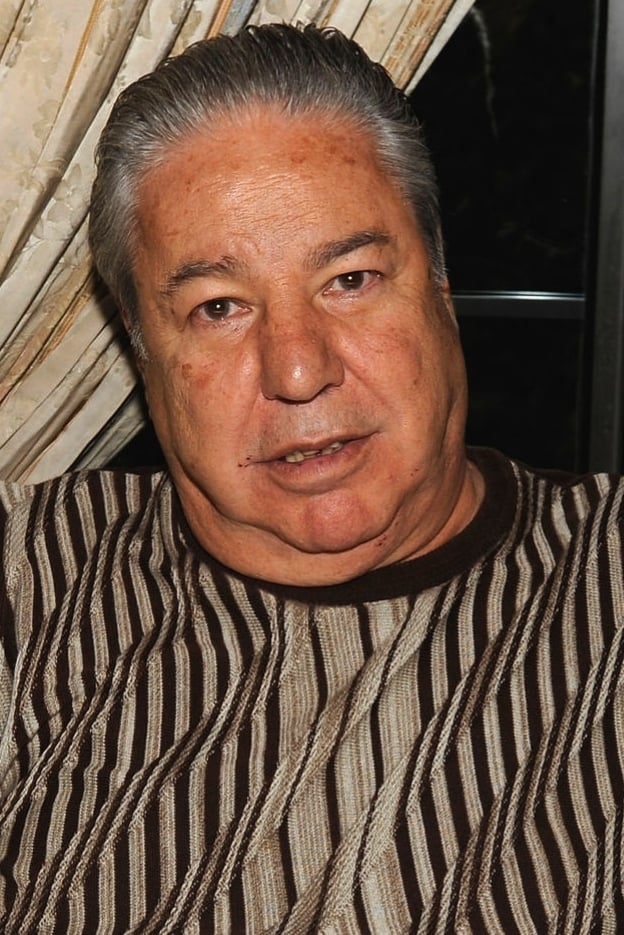

A head reportedly worth $1 million to somebody

He served a hitch in the Army while maintaining mob contacts. Once home he got back in the game, until he was sent to prison for 10 years for extortion. Out after four years, he used his prison contacts to expand his drug business. Arrested in 1980 for trafficking in narcotics — he was an addict and alcoholic — and a substantial suspect in a theft from Lufthansa Airlines, Hill was convinced he was on a mob hit list. With trouble from both ends, Hill turned informant. His information eventually led to 50 convictions. He and his family entered the Witness Protection Program, which seems wise. His wife left him in 1990; in the early '90s he blew his cover, including arrests for burglary, assault, and three DWIs, and was kicked out of the program; in 2001 he was arrested on narcotics charges; and according to ABC News, the mafia put out a $1 million bounty on him.

Some say Hill turned a new leaf in his later years, selling his own brand of spaghetti sauce online and frequently calling the Howard Stern Show. He took classes to become a drug and alcohol counselor. He created paintings. But June 12, 2012, Hill died in Los Angeles, not from a mob bullet, but from heart complications related to smoking, according to his obituary in the LA Times. He was 69.